There is clearly a lot to be learned about medicine from history.

Indeed many effective treatments can (and have) been identified not by close examination of the human body, but but the close observation of patterns in statistics.

Thus is is possible with good data, a good eye, and quite a bit of spare time, to see many of the contributing factors to disease or accidents. The famous cases include the realisation that the plague was carried by rats and that cholera was in the water. Thus was born the science of epidemiology.

I think if I was starting university again right now, there is a good chance I would have steered towards that as a profession – for it has saved countless lives, and can be done from the safety of a nice desk, replete with good coffee and a supply of biscuits. I have never been drawn to a life of tending to the ill or injured, so this would have been a nicer way to get my benevolence ‘hit’.

Alas, I studied engineering, and though perhaps I could use epidemiological methods to predict metal fatigue or bridge collapses, I am not sure that would be very useful. We engineers seem to spend much more time looking at the costs of making something, and then the price you can sell it for.

Anyway, time for the science bit…

Epidemiologists looks for patterns relating illnesses to other things: other illnesses, location, professions, exposure to animals, and many more.

There are some pretty major trends in health happening right now. For a good example, look at Hans Rosling’s presentation at TED recently. He shows, among other things, that people are living longer than ever before. Despite all the talk of the world going to pot, it seems there is an untold story – the story of how life expectancy in the developing world has been climbing beautifully for several decades. The stats tell a story of a golden age in humanity.

To go off on a slight tangent, I have to say what a pity it is that the media focus so much on the wars and tragedies. Of course, they sell sensation, so they will continue, but we humans are not used to getting news from the whole planet – we have barely got out of the trees and only left our small villages for cities an eye-blink ago. Evolutionarily speaking, our fears were programmed in a much smaller environment where news did not travel very far – the story of a death would be significant because you didn’t know very many people. Nowadays we get more news and we also know far more people because of the world of celebrity (blame the media again), and because we are so ‘networked’ (its the ‘new’ media this time) we also know a huge number of people by association. Thus we receive bad news far more often and tend to overvalue its direct threat to us.

Now let me get back on track. We are living in a golden age – better nutrition, cleaner water, the understanding of the theory of germs, and of course, advances in medicine (think vaccines, think penicillin, think surgical methods). We have benefited hugely from a better understanding of how the body works and of how fungi, bacteria and viruses work.

The activity is higher than ever on countless fronts: dementia, HIV/AIDS, epilepsy, stroke, heart disease, and so on… but what about the big kahuna? I refer of course to cancer.

Well it has not been cured. The ‘cure for cancer’ has long been held up as the iconic challenge to medical science. Only trouble is, the challenge is flawed. There is no one ‘cancer’ – there are many different cancers – and the little bastards are all subtle and complex – and even if you can kill one, killing it will often kill off something else, because cancers are not as alien as say viruses – they are in fact our own cells turning on us.

So rather than looking at cellular function and cunning ideas like rna interference, what can we do with epidemiology?

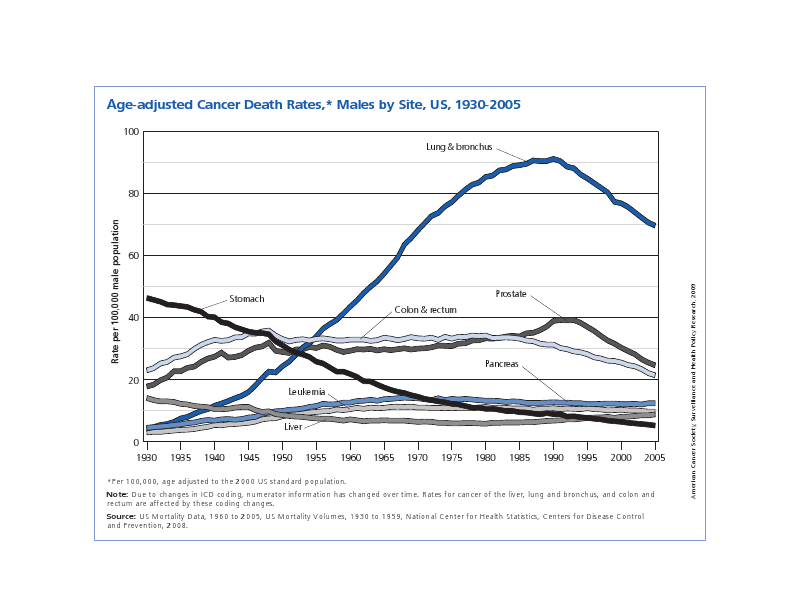

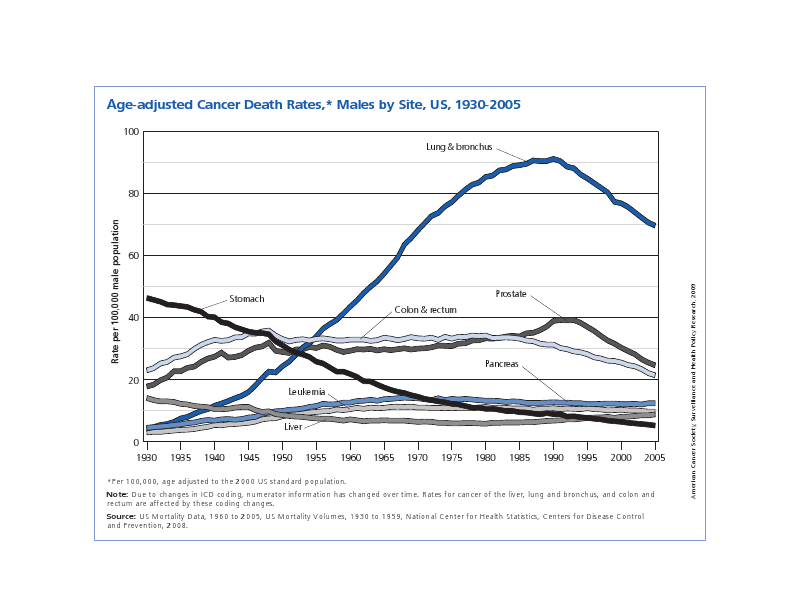

Cancer death rates are not independent of the death rates from other causes...

Yes, cancer is not an ‘epidemic’ – we are not studying its spread, but we can certainly study correlations and seek causation (think smoking tobacco or working with asbestos). Smarter people than I are already poring over this sort of data, and there is much hand-wringing nowadays because the ‘easy’ causes have most been found and now we are looking at the weaker correlations, where the link is not certain, or where the sacrifice to benefit ratio is unclear. Think barbecue meat, think E numbers and so on.

But I don’t want to talk about that sort of cause. What I am wondering is relates more to age…

Cancer is somewhat a statistical process – it may arise as a random mutation, which, as fate would have it, is also bad for one’s health. Many mutations result in no effect or perhaps cell death or perhaps just reduced function of the cell. There are very few mutations that actually allow for continued (and sometimes rampant) growth and macro level harm. As the mutation is a random event, the chance of occurrence will depend on the number of ‘cellular events’ that occur in a lifetime – this is determined by two factors, the frequency of the events – and the length of the lifetime.

Now add to that randomness the fact that many cancers are slow growing – they may take too long to harm or kill you and something else gets you first.

These two factors together go to show you that the longer you live, the greater the risk of cancer development. Add to this the probable third factor that older cells are more likely to go haywire, and you can easily see why cancer is more commonly suffered by older people.

Does this mean that you risk of ‘catching’ cancer ‘today’ is less if you are younger? Well yes, if your cells (or immune system) are in better shape, mutations may be rarer and you may fend off some that do occur – however, your chance of ‘having’ cancer (rather than ‘getting’ it) are accumulative with age, so this is a very strong factor when looking at screening (looking for cancers that already exist). It is often only worthwhile screening for cancer in older people where the ‘hit rate’ makes the costs (false positives) justifiable.

This age affect is well known, but I am wondering if another factor may be throwing a curve ball into the stats – the longer lifespan of people generally.

As some types of cancers are being treated more effectively (prevented/slowed/cured), and as death from other causes (heart disease, pneumonia, tuberculosis, etc.) drops, does that not give cancer more fertile ground to wreak its havoc?

In other words, will curing other ailments, to some extent, tend to push us into the waiting arms of cancer?

And if this is already happening, perhaps the cancer death rates, hiding underneath the massive advances there may actually be an underlying increase in death from cancer due to the increased survival of everything else.

———————

So! We all die of something eventually. I guess the question medical science now needs to ask is: what is the best way to die? Should we be saved from one death only to have another? Will cancer rates start to creep up again as advances against cancer slow and lifespan continues upward? Time will tell!

You see, over the next couple of minutes, we’ll see that a human body is not much different to, say, a tractor. It’s a tough machine and just like a tractor has very few needs – a little fuel, a little air and a little water.

You see, over the next couple of minutes, we’ll see that a human body is not much different to, say, a tractor. It’s a tough machine and just like a tractor has very few needs – a little fuel, a little air and a little water.