I have been keeping my eye on the evidence that ‘life experience’ can be passed on in your genes.

It has been proposed many times as a mechanism of evolution, and indeed was considered likely before the concept of ‘selection’ was understood. It’s attractive because saying that ‘survival’ is the one and only way to adding value to the genes seems, well, wasteful.

Surely, you’d think that a fear of snakes based purely on the idea that people who were not afraid of snakes were ‘taken out’ of the gene pool by snakes, is less efficient than a mechanism that captures experience – that snake killed my dog, I should avoid snakes, and so should my kids…

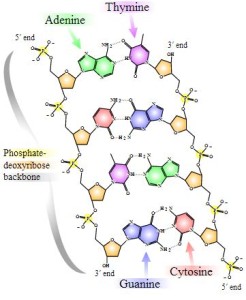

However, once DNA was understood and shown to be dense with what seemed to be all information that could ever be needed, dissent waned to an all time low. The mechanisms of DNA were pretty clear – your DNA was set at birth and while it might mutate a little randomly, had no way to ‘learn’ from your life before being combined with a partner’s to create offspring. The case seemed pretty settled.

There remained niggles though. I worried about the speed of evolution as we have so very much to learn and so little time to evolve! So I looked for ways evolution could amp up its power. It seemed to me that nature, so darn clever at self-optimisation would make improvements to our design based on non-fatal experience, or indeed passive observation.

Others similarly concerned continued, often in the face of deep scepticism, to study what is called epigenetics, the science of heritance not coded by DNA – and thus having the potential to be edited during our lives.

I first heard about it around 10 years ago when media reported that the actual DNA sequence was not the only way info could be stored in cells – in theory the histones present can affect how the DNA ‘works’ (how genes are ‘expressed’) and their presence could thus change the characteristics of any lifeform coded therein. The type and number of histones may be few (relative to the number of base pairs in DNA) however, the many locations and orientations they can take create a fair number of possible combinations and permutations.

When I heard about this theory, I was put into a state of high curiosity. On the one hand, it was a little blasphemous, but on the other hand tantalising. If nature could find a way to combine the power of selection with the potential benefits of life experience, we could get much faster and more effective evolution.

My curiosity was soon rewarded with another possible mechanism for smuggling info to the next generation. DNA methylation – the idea is that DNA can host little ‘attachments’ in certain places. These may be temporary, and reversible, but they have now been clearly shown to alter how the DNA expresses itself.

On the face of it, the evidence that DNA expression is environment dependent is rather strong, but the idea that the environment around the DNA coil actually contains consistent and persistent intelligence picked up during our lives is much harder to prove.

And so teams have been beavering away trying to get to the bottom of this, and this week one such group has fresh news for us. A Nature Neuroscience paper has tested the theory in a rather clever way.

They started by teaching some mice a new fact (that a certain smell would be associated with trauma) and then later, tested their kids. Lo and behold the kids whose parents had been taught fared significantly better in the test than untrained, unrelated mice.

They started by teaching some mice a new fact (that a certain smell would be associated with trauma) and then later, tested their kids. Lo and behold the kids whose parents had been taught fared significantly better in the test than untrained, unrelated mice.

This may sound a little trivial, but you must remember that the current ‘popular’ understanding of genes is that they only gain intelligence by surviving – or more precisely they shed stupidity by dying. However, here we are seeing information pass between generations without the need for anyone to die.

Furthermore, because of the carefully selected lesson taught to these mice, the researchers were actually able to see that a specific part of the DNA, while not different in design was nevertheless more active.

Now, I do not know enough about DNA to double-check this claim, but you can rest assured others will – because that’s what journals are for – and in this case the implications are huge.

—————

Like what, you ask?

Well, off the top of my head, it means that much of what we do between birth and reproduction will affect all our descendents – this undermines the idea that one’s body is one’s own to do with as one pleases.

It also indicates that there is potential for us to deliberately control the expression of our DNA, allowing us to do some genetic engineering without actually changing the DNA sequence.

More importantly, and more controversially, it would mean natural selection would not need to explain all the marvellous diversity we see around us on its own.

It remains to be seen what proportion of our ‘design’ is coded for outside the DNA, or indeed how much this mechanism can improve or speed up evolution, however I for one hope it works out to be right and that mother nature has indeed figured out how to seriously boost the power of selection.